Supreme Court Tackling Intellectual Property "Fair Use" In Multiple Contexts

01.10.23

Two cases involving the scope of the “fair use” defense to allegations of intellectual property infringement have made it to the Supreme Court’s docket and are set to be ruled on early this year. The first arose in the context of copyright law and whether a use was “transformative,” while the second focused on trademark law and whether a use was “parody.”

In both instances, the Court must address whether and to what extent a new work that incorporates elements of another’s original work is so changed that it does not constitute an infringement of the original, but instead is fair use and protected under the First Amendment. Despite two different areas of law being involved, the examination in each case is quite similar. It is likely that the Supreme Court’s decisions in these cases will simultaneously affect both areas of law.

Copyright: Is the Work Transformative?

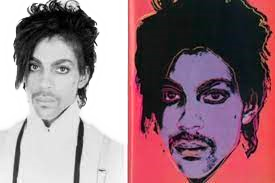

The first case involves a dispute over a photograph of Prince that was used in a silkscreen print by Andy Warhol. The original photographer brought a claim against Warhol’s estate, claiming copyright infringement. The question before the Justices was whether the new work was transformative enough that it conveyed a new meaning or message to the audience.

Fair use is a doctrine that protects use of copyrighted work for certain purposes, such as criticism, parody, news reporting, and educational purposes. Fair use also can be found outside of these purposes, including when a work has been so transformed that it constitutes a new work serving a different purpose. The copyright owners of the Prince photo argued that the new work constituted a derivative work of the photographer’s image, which is an exclusive right of the copyright owner. The Warhol Estate argued that when Andy Warhol applied his creativity, the image of Prince was transformed into a grander artwork that conveyed a different message than the original photograph. According to the Warhol Estate, by that transformation, the Warhol work was not a derivative, but rather a new expressive work protected by the First Amendment, and any incorporated elements of the original work was “fair use.”

In the oral hearing, the Court recognized that the key question involves a side-by-side analysis as well as the determination of whether the new work conveys something different. The Justices seemed hesitant to take on the role of “art critics,” implying that such an inquiry should be left to evidentiary support.

The ruling will undoubtedly have an exceptional effect on the future of using pre-existing work in another manner, such as when books are made into movies, or when musicians use portions of old songs when making new work. As the Court seemed to recognize, the danger presented in the Warhol case is that “famous” artists might get a free pass because the art world has deemed their work to have artistic merit, while an unknown artist—without the cachet of someone like Warhol—could be labeled an infringer for engaging in the same activity. Oral arguments were conducted in October, but a ruling is not expected until early this year.

Trademark: Is the Work Parody?

The Supreme Court has also agreed to hear a case involving the maker of a rubber squeaker dog toy coined the “Bad Spaniels Silly Squeaker”. Whiskey maker Jack Daniels argues the toy infringes on its various trademarks. The question presented is whether VIP Products, the company behind the toy, is protected from trademark infringement by the First Amendment’s freedom of expression.

Similar to copyright law, infringement of a trademark generally rests on a side-by-side analysis of the two marks. At a glance, the two products may look quite similar. However, as the Ninth Circuit stated, the Bad Spaniels toy mimics the Jack Daniels bottle but with “lighthearted, dog-related alterations,” such as the obvious “Bad Spaniels” spin on “Jack Daniels,” “Old No. 2 on your Tennessee Carpet,” “43% Poo By Vol.,” and “100% Smelly.” The toy’s physical appearance also reflects that of the bottle’s design, which is trademarked by Jack Daniels.

VIP has never disputed the claim that they copied elements of the Jack Daniels bottle. Instead, they contend that they made material humorous changes to render their dog toy a parody, and thus a fair use under the Trademark Act. Like in copyright law, fair use is one of the most common defenses to trademark infringement. It allows a legal defense to an infringement claim if the use of another’s trademark is done for the purposes of commentary, criticism, or parody, rooted in the public’s First Amendment right to freedom of expression. Critically, however, case law has traditionally been skeptical of parody and usually the analysis focuses on the message of the parody being integral to the use of the source material. Courts have routinely noted that “funny” does not equal “parody,” and simply because something is humorous does not transform the use into a protected “fair use” parody.

What This Means for Intellectual Property Law

While the two cases consist of different forms of intellectual property, they share a commonality in that the outcome of each case is largely dependent on (1) a side-by-side analysis of the changes made from the original to the new work, and (2) a determination as to what those changes convey to the consumer/audience. These types of inquiries rely more on human judgment than legal analysis, and because of that the Supreme Court proceeds with caution in choosing to hear them. Given that the Supreme Court was reluctant to play “art critic” in the Prince case, there is a high likelihood it will be hesitant to play “comedy critic” as well. In the Bad Spaniels case, the Court may instead focus on whether there actually is a message being conveyed, and if the use of the trademarked material is necessary to convey that message.

The Prince case, which will likely be ruled on first, should provide a good preview of what direction the Court will lean in the Bad Spaniels dispute. If the Court finds that the Warhol print is protected under fair use, it’s very likely that the Bad Spaniels toy will be afforded the same protection, as the Prince artwork incorporates much more of the protected work than the dog toy.

Courts at all levels are constantly walking the balancing line that forms the foundation of intellectual property, which is to promote creativity in science and the arts, while still providing a level of protection and rights to original creators in their work. Lawyers too struggle with applying the fair use standards and advising clients as to “how much is too much?” or, conversely, “is the work changed enough?” Hopefully, the Supreme Court’s decisions in each of the foregoing cases will assist the Bar in approaching these “fair use” situations with greater certainty.

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., Petitioner v. Lynn Goldsmith, et al., No. 19-2420 (2nd Cir. 2019)

Supreme Court Docket No. 21-869

https://www.supremecourt.gov/docket/docketfiles/html/public/21-869.html

VIP Products LLC v. Jack Daniel's Properties, Inc., No. 18-16012 (9th Cir. 2020)

Supreme Court Docket No. 22-148

https://www.supremecourt.gov/docket/docketfiles/html/public/22-148.html